Motivations

Designing a real time networking protocol such as Unity’s NGO or the Photon Engine is certainly no easy feat, and there may be a sense of misplaced confidence to think that one could top existing battle-tested frameworks. General purpose multiplayer networking frameworks were traditionally motivated by remote authoritative server or relays for which bandwidth optimization is of the utmost importance. Latency, while still a priority, is secondary to bandwidth concerns which have immediate monetary implications. In fact, considering that a latency of 100 ms is considered to be acceptable in casual settings and that modern networking frameworks easily meet such benchmarks, it may be hard to justify rewriting a networking library from scratch unless our application calls for absolute minimal latency. In our case, since we were developing a co-located mixed-reality application, we did in fact encounter unique challenges that required latency minimization beyond what’s available in typical commercial and open source solutions.

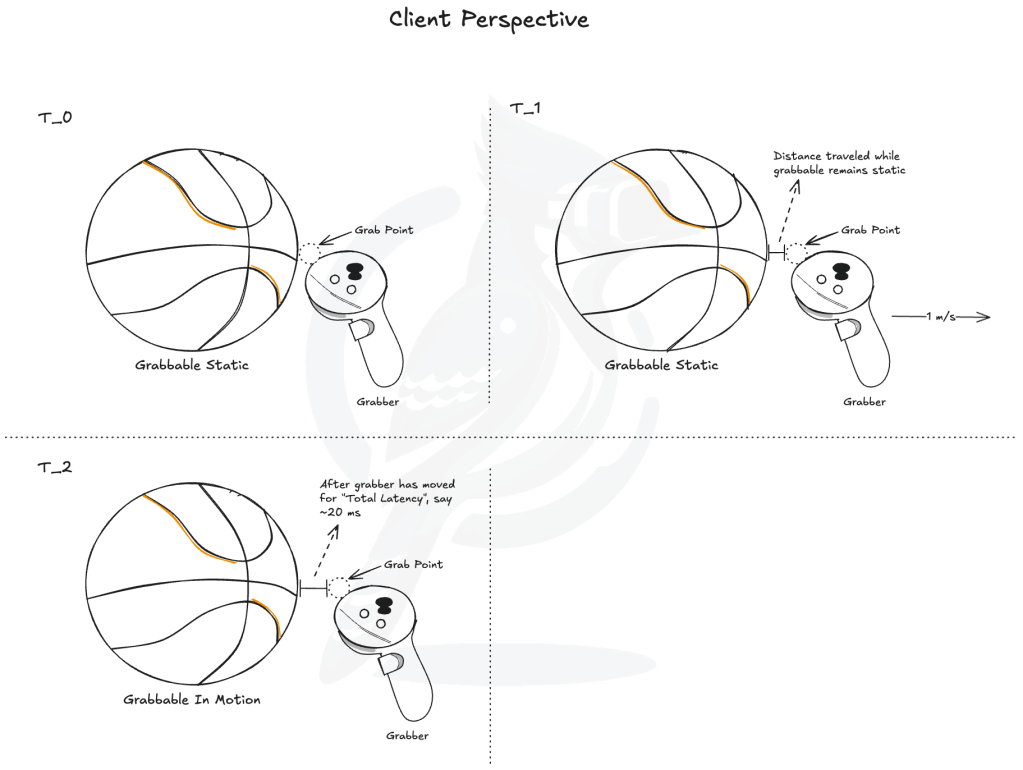

A unique parts of XR is manipulating virtual objects in space through a controller or hand-tracking. On the other hand, in desktop games, players might interact with their environment through their mouse and keyboard. Engineering wise, both are practically the same as players are simply sending either movement deltas or absolute positions of their peripherals. Yet, despite such similarity, XR calls for a higher standard in latency due to visual perception. Take for example Figure 1, where we have a virtual grabbable object, a basketball, which responds to pose updates of its grabber. The diagram is drawn from the client’s perspective, so the grabber will appear instantaneous to the client since it will be updated through direct hardware API calls. Assuming no client-side predictions, the basketball’s position will be updated only when the client receives a network update from the server. Because the basketball’s pose is updated upon receiving the server’s network objects stream, the client’s observation of the basketball at any point in time is a state that happened strictly in the past by several milliseconds which ultimately leads to a visible gap between where the object should be and where it’s perceived by the player.

Figure 1.

To see why, assume that at time T_0, the grabber has been sitting idly for a sufficiently long time for the basketball to appear static. In order for the client to see the effect of their actions on the basketball’s pose, it must wait at least network round trip time (RTT) plus some processing time on the server’s end, a combination we could call “Total Raw Latency”. Now let’s say that the client is moving the basketball at a walking speed of 1 m/s. Between T_0 and T_2 (which occurs when the first moving frame is received) we’d have T_1 when the grabber will have traveled an observable amount of distance while the basketball is seemingly static. Then finally at time T_2, the client will have gotten the very first frame from the server where the basketball is no longer at the same static pose and from that point onward, the basketball will seem to move at 1 m/s towards the grabber maintaining the observable distance gap achieved from T_0 to T_2. Finally, assuming an average total raw latency of 20 ms, the distance gap would be a visible 2 cm, which is almost an inch in imperial. Knowing that’s just at a walking speed, we can finally see why a naive implementation of the server authoritative model can be limiting in XR settings where one might have reflex based activities like table tennis.

Given such limitations of the server authoritative model for XR applications, we want to eliminate alternatives, But to start in favor of server authority, we can argue that it is conceptually very easy. At the core of the model, both the server and the client each send steady streams of information. The server sends regular updates of existing network objects’ transforms and perhaps some custom metadata. The client on the other hand sends updates of their controller and headset positions. Then, right on top of that we have the RPC (remote procedure calls) layer, where both the client and the server can send one-off messages to each other. A robust RPC layer would allow the clients to send controller inputs and the server to initiate audio and visual effects, thereby enabling friction-less bidirectional interactivity. With multiple clients, each client receives the same game state from the server, meaning clients can be synchronized among each other with no extra effort other than initiating contact with the server.

What about alternatives like P2P or client authoritative frameworks? P2P protocols like those used for fighting or RTS games, the game engine is required to be deterministic, because each player must step through simulations based on each others’ inputs. It can be delay-based where a player must wait for the other player’s inputs to continue the simulations, or rollback-based where a player could predict the other player’s inputs but re-simulate if the predictions turned out to be incorrect. In contrast, in our current production of Infinite MR Arcade, we are building a co-located mixed-reality physics sandbox using Unity. Unity’s physics engine is technically not fully deterministic, so the only way to get lockstep protocol to work is if we designed our own deterministic physics engine and simply use Unity (or any other popular alternatives like Unreal or Godot) as a rendering engine.

Even then, lockstep as a concept is fairly incompatible with XR requirements. Lockstep with rollback works really well for Fighting and RTS genres, because input types are fairly simple key presses along with basic joystick axes. It’s easy to make predictions if all we have to worry about is if the other player is holding onto a button, or simply staying idle. In XR, not only do we have button inputs and joystick axes, we also have 3D controller poses (position and rotation) as well as IMU measurements such as angular velocity and linear acceleration. More importantly, in the former, fairness matters way more than smooth experience. So not only does the potential limitations of lockstep protocol simply not even matter for Fighting and RTS, the input types they deal with make the simulations fast enough anyways. Lastly, although lockstep can be designed to work with any number of players, the number of players must be predetermined and every player must be online so that simulations can continue. That means that it is highly challenging to add and remove players during the middle of a game. Scalability with lockstep is a huge crutch in adapting it for XR experiences, but it remains as an interesting alternative.

Finally, what about client authoritative models? Social games like RecRoom and VRChat all use a client authority heavy design with central relay as its infrastructure. When a client “owns” a network object, they are the ones responsible for locally simulating the object and reporting the state changes to a relay or authoritative server, which would then broadcast the changes to the rest of the players. In many cases where latency is an issue, client authoritative models can be a great way to hide a lot of the latencies, but the latency doesn’t just magically disappear. While one player owns an object and sees it as if they can affect it in real time, other players would still feel the latency.

Although that is acceptable for a social hangout type of games – and with careful designs, even fast-paced real-time game-plays could be made possible – it still doesn’t solve the issue of authority transfer logic. Within well-defined scopes such as real-time 1v1 matches or turn-based table top games, it is possible to lay out exactly when ownership over objects have to be transferred among the players. However, for a physics sandbox with an undefined number of players, that becomes a little tricky. Let’s say that there are three players in a session, two of them are playing table tennis, and the third is simply observing them. In a strictly 1v1 session, with players strictly identified as players or observers, if one player serves or returns another player’s serve or hit, they can notify or initiate a transfer of ownership. The server would know to transfer the authority to the other player and not any of the observer(s). Observers simply have to update the ball and paddle poses as they come in from the relay.

In a sandbox context, however, where everyone can interact with any object in the scene, even with a central authority server, it’d be impossible to tell who should own the ball as it flies off of a player’s paddle. Maybe you can encapsulate the client authority model within the larger server authoritative model by enforcing player signup prior to starting a match and accurately keeping track of who is playing what at any moment. That’s absolutely possible, and probably a very common and good enough solution for VR social games with interactive mini games, but for a local multiplayer with a significantly higher budget for bandwidth and latency, there’s no need to over-complicate.

Taming the Impossible

Now that we finally covered some background and motivations, I wish to provide just one of many concrete examples of how we made strictly server authoritative design viable with respect to latency. The core idea was a common sense “greedy approach”, which involved the following best effort steps:

- the client must send out controller updates as soon as it is available,

- the server must propagate the controller updates through some arbitrary chain of updates as soon as it receives it,

- the server must send out the resulting game state (which reflects the client controller update) immediately,

- and finally the client must receive the new game state as soon as possible and immediately render it.

In our first working implementations, we observed around 30-40 ms of total latency. It was good enough for placing decorative objects around the scene and throwing darts with no considerable jitters. However, with the addition of reflex based items like table tennis and air hockey, we were starting to face higher standards for latency. In an age when online game services are providing sub 20 to 40 ms of ping, 30 to 40 ms latency over LAN, even wireless, seemed to be over what is theoretically achievable. At this point, we knew that we had to establish a tangible model for the theoretical limit.

After significant experimentation, we’ve finally arrived at a satisfactory model. Following are the assumptions of the ideal model:

- Network round-trip time (RTT) is a fixed average with a one-way trip being half of RTT.

- There is no time cost to update/tick.

- All update cycles will be abstracted as a single clock, where 1/FPS = Delta Time = Tick Interval.

- Server and client clocks are not guaranteed to be in any sort of sync.

- Client message must wait until the next closest tick to be processed.

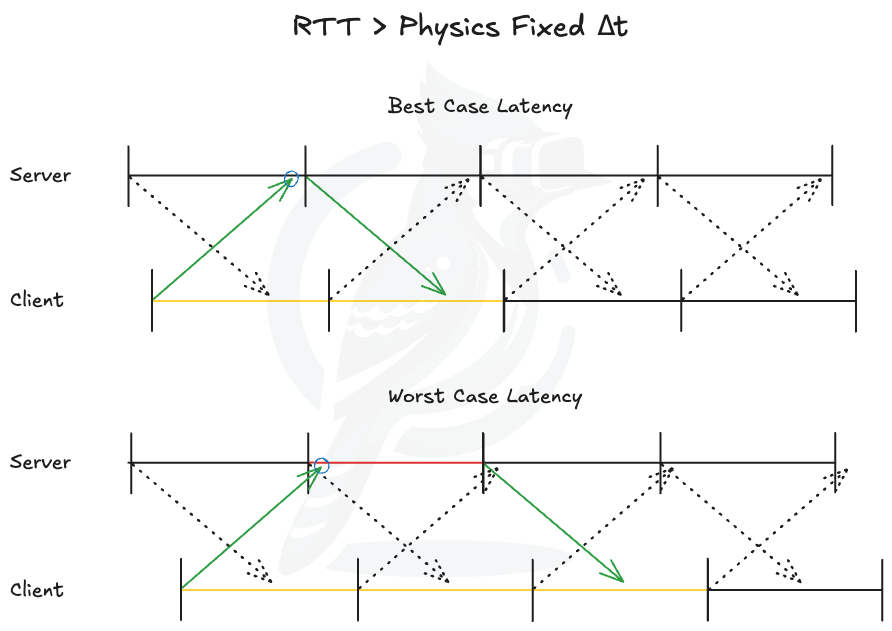

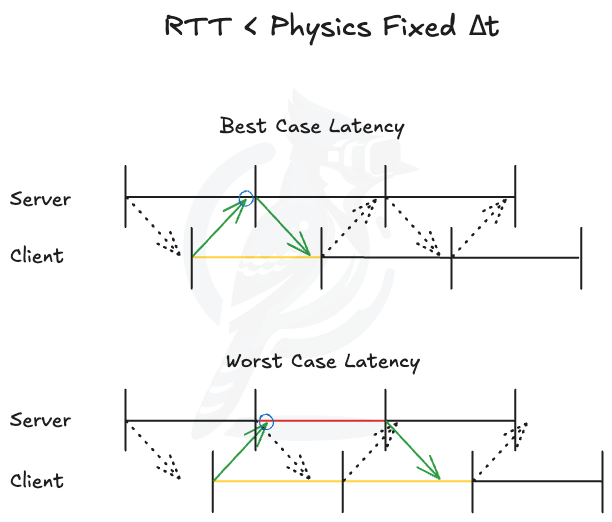

Figure 2. RTT > Physics Fixed Delta Time

Figure 3. RTT < Physics Fixed Delta Time

Because there is no guarantee in client-server sync, a client’s message can arrive at any point during a server’s update cycle. Since, the server’s life-cycle happens in intervals of delta time, the longest a message would be sitting in queue would simply be delta time, with the shortest being zero. With no other source of delay, the best total raw latency in the client’s perspective is RTT and the worst total raw latency is RTT + Δt, where Δt is the maximum delay resulting from server side processing. To get the final lower and upper bounds, however, we do need to round up those bounds to the nearest multiple of delta time, because the client also update/renders in intervals of delta time.

Best Case Perceived Latency:

Lbest ≈ ⌈RTT/Δt⌉⋅Δt

Worst Case Perceived Latency:

Lworst ≈ ⌈(RTT+Δt)/Δt⌉⋅Δt

= ⌈RTT/Δt + Δt/Δt⌉⋅Δt

= ⌈RTT/Δt + 1⌉⋅Δt

= (⌈RTT/Δt⌉ + 1) ⋅Δt

= ⌈RTT/Δt⌉⋅Δt + Δt = Lbest + Δt

As simple as that! Hopefully figure 2 and figure 3 serve as visual justifications of this model. We could also confirm that Lworst is approximately Lbest + Δt by envisioning the client clock graph in either of the best case diagrams sliding leftward until the end of first half RTT arrow infinitesimally approaches the nearest tick to the left. Now let’s see this simple model in practice.

Assume we’re working with 120 FPS, which yields approximately 8.33 ms per frame, and suppose we had an average RTT of 10 ms. That means our lower and upper bounds according to our little formulas would be 16.67 ms to 25 ms. Previously I revealed that our first implementation of our networking stack yielded around 30-40 ms of latency. In our project, we used an even higher frame rate and measured an average RTT slightly lower than 10 ms (I must emphasize again that this is all wireless), which points to the fact that 30-40 ms of latency was severely over what was theoretically achievable.

Not only did this model confirm a need for optimizations, it also told us what was specifically in our control as developers. Stepping through our assumptions, we can rule out two points, which are RTT and clock synchronization. Yes, clock synchronization can be achieved using something conceptually similar to an NTP server, but that would be an unreasonable burden on the users. It would also require that the game engine maintain a strict temporal interval between fixed updates as well as extend the ability to shift or delay this update cycle to match the client’s clock against the server’s to achieve the best-case total latency given some average RTT. Even then, the inconsistent nature of RTT would lead to a collapse of this approach.

However, there are two remaining factors that we can still control, which are update frequency and non-network sources of delays. Regarding update frequency, if we increase the tick rate, we decrease the delta time, thereby causing a downward shift of the minimal latency range. That’s a simple, obvious optimization, but the trade-off would be increased network packet transmission rate and increased chances of burst traffic. On the other hand, reducing non-network delays is a straightforward idea but requires heavy architectural decisions and meticulous planning. On one level, non-network delay can come from greater than expected amount of computation, but that’s generally in the hundreds of microseconds scales and maybe up to 1-2 milliseconds especially during GC. Unless the codebase was written very poorly, this aspect of non-network delay is just a source of minor jitters, not a persistent increase in latency.

The true concern regarding non-network delays is delays occurring from interdependence. In XR, we are primarily interested in grab interactions where objects can be classified as grabbables or grabbers. By leveraging separation of concerns, we treat grabbables and grabbers as independent agents with their own responsibilities and reactions to environmental stimuli. This modularity enables flexible extensions such as permission rules, autonomous behaviors, and complex interaction patterns. However, the issue with this design is that if a grabber’s transform is updated and we don’t set up an explicit pipeline for a grabbable to respond to its grabber’s transform update, we’d have to wait until the next frame to see guaranteed changes to grabbables.

We bring up the term “guaranteed”, because by default Unity only provides FixedUpdate, Update or LateUpdate, and for something like grabbables and grabbers, we prefer FixedUpdate to step through their state machines. However, because we have no way of guaranteeing the ordering of gameobjects’ fixed update methods, we cannot guarantee that a grabbable will execute its block of fixed update immediately after its grabber’s. Therefore, if we previously had 16.67-25 ms minimal total latency range, then due to grab interaction interdependence, we’d instead be looking at 25-33.33 ms.

To make matters worse, we have two additional sources of inefficiency, first being the client’s controller broadcast, and second the server’s game state broadcast. Because the client’s controller poses are updated through API calls, we don’t have flexible control over when these updates get called. We generally lack the ability to force a client controller broadcast following a pose update leading to an additional frame of delay. Similarly, because a server’s game state broadcast is also run on FixedUpdate, by the same logic, we get another frame of delay. All in all, that’s a 41.67-50 ms minimal latency range! That clearly supports our initial observations.

So how do we address this? Well, regarding grab interaction, the standard approach seems to be to have a grabbable subscribe to a grabber’s “OnGrab” so that the grabber can explicitly update the grabbable’s transform. At first I thought this might be bordering on tight coupling, but for a long chain of interactions where each entity can simultaneously have a grabbable and a grabber, the standard approach seems to be a fairly strong solution, although we’d have to watch out for cycles. (On a more technical note, we could take a similar approach to client controller broadcast by subclassing OVRCameraRig and overriding its FixedUpdate.)

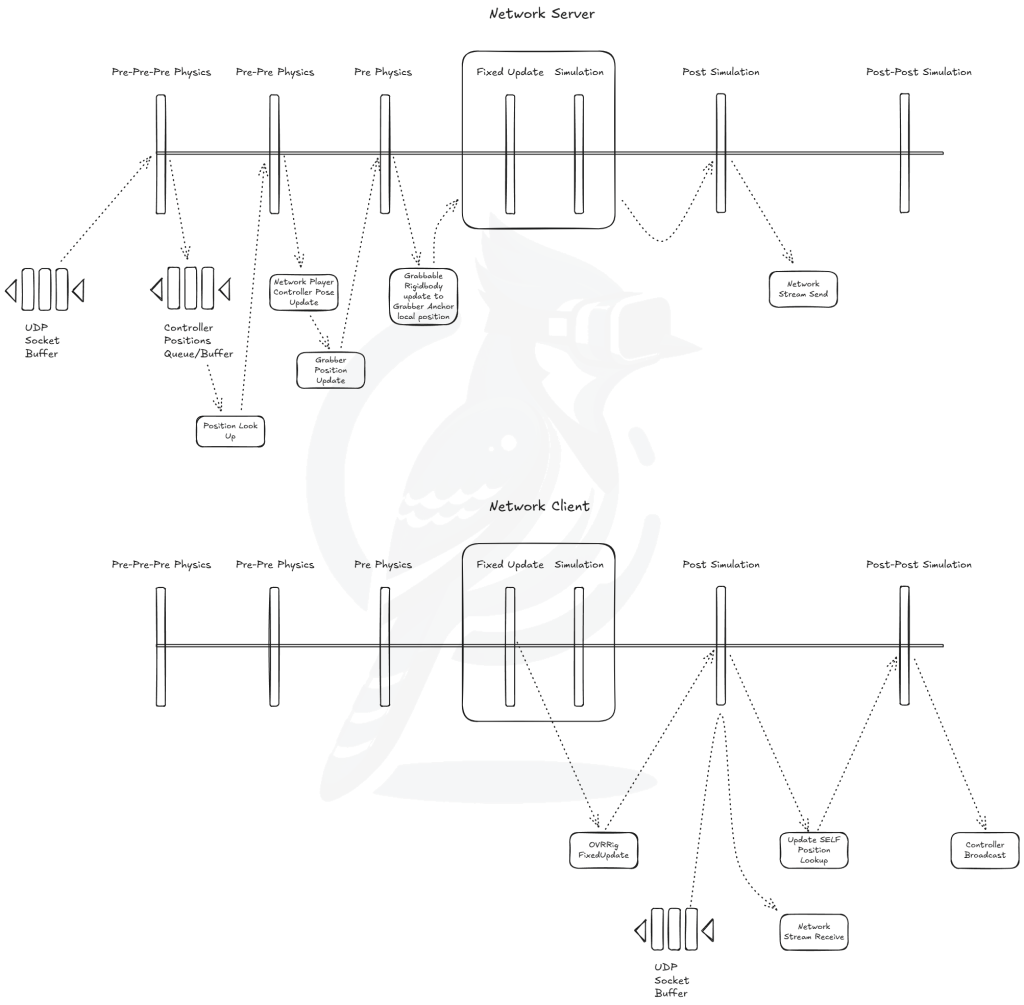

Unfortunately for server game state broadcast, we need a slightly different solution, because a game state broadcast should only be made when all objects have been properly updated and the physics simulation has run. So even if we somehow hacked together a way to have the last updated object invoke the broadcast, that can only happen before a physics simulation is actually run. So in order to be able to send a broadcast immediately after physics simulation, there’s no way around having to inject a new update block following a physics fixed update by using Unity’s relatively new low-level API. Since in our Infinite MR Arcade we don’t have too chaotic of interactions and we have to add a new playerloop anyway, we decided to just kill three birds with one stone by coordinating fixed updates using PlayerLoop, which is illustrated by Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Finally, after making all these adjustments, we were able to achieve a measured total latency between 9-13 ms! You can see this for yourself by trying out the co-located mode on our Infinite MR Arcade. Just be aware that as of patch 1.2.8, we have interpolation on decorative objects (not on shapes yet), so there will be slightly higher latency on them, but we also have a custom interpolation technique to keep the latency nearly true to minimal latency.

As I have just hinted, there are many more techniques involved in bringing out realism in a co-located experience. In this article, we have not yet covered interpolation or dealing with burst traffic in general. We also haven’t covered how to create a bidirectional, low-latency, high-throughput, and reliable RPC system, which sounds ridiculous but can be achieved in local networks due to increased bandwidth budget. Based on how much time I have outside of active development and maintenance, I’m hoping to write articles on those topics as well.

Jay Oh – 01/17/2026

Leave a comment